Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month

May is Maternal Mental Health Month, which provides an opportunity for providers, patients, communities, and activists to engage in discussion and dialogue about the importance of recognizing maternal mental health as an unmet, urgent public health need.

Posted under: Maternal Health, Mental Health

“I couldn’t bring myself to tell my doctors or nurses, or the doctors and nurses in the NICU about the way I was feeling. I was already that “bipolar patient.” I had used opiates for a few years to cope with the pain that depression brought with the disease. I could feel myself becoming more and more depressed and desperate for help, but thought that if I asked for help, my baby would be taken away from me. My bipolar disorder had haunted me for most of my adult life, had labeled me, and now with a new baby, had no one to reach out to. Each time I left the NICU, I thought it would be the last time I would see my baby. That feeling was so traumatic, and even though my baby is now 1 year old, I still relive that fear every day.” –A.R., during a postpartum interview

Overview

May is Maternal Mental Health Month, which provides an opportunity for providers, patients, communities, and activists to engage in discussion and dialogue about the importance of recognizing maternal mental health as an unmet, urgent public health need. Compound this maternal mental health need with the public health crisis of racism and a stark picture emerges of women and birthing people in need of tremendous support. There are many facets that must be addressed within maternal mental health—access to care, transportation, stigma, insurance coverage, stable housing, to name a few. An area of concern that has been identified is that of opioid use disorder during pregnancy. A greater prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, physical and sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and chronic pain disorders likely contribute to disproportionate rates of opioid use and misuse in women and particularly women during pregnancy. Beyond opioid use are other substances that are used frequently to mask mental health symptoms that can be treated by other means. But that treatment costs money and access can be sparce depending on location and availability of providers.

The National Perinatal Information Center continues to track maternal mental health outcomes, including substance use disorder. In 2019, substance use disorder (ICD O99.3XX) was coded in 1.9% of patients (n = 334,402) and by September 2023, 2.3% were coded with substance use disorder (n = 325,195). While that number might not seem high, it continues to reinforce the need to remain vigilant in assessing patients in the prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum period.

In the time period October 1, 2021 through September 30, 2022, 30-40 patient records were coded with postpartum psychosis (ICD -10 F53.1). In seeing this information, I thought about the patient behind the data. I wondered what their support systems were like. I wondered if they had support, or if they were alone in their suffering. I hope these women had what they needed to not only bring life into this world, but also had those to support them while they nurtured that new life.

Maternal mental health directly impacts the outcomes of a newborn. Perinatal mood disorders are some of the most identified maternal mental health concerns and are associated with increased risks of maternal and infant mortality and morbidity and are recognized as a significant patient safety issue. In addition to perinatal mood disorders, there are other mental health diagnoses that must be appreciated, including pre-existing psychiatric illness (major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, etc.) that often is underreported and undertreated due to stigma and fear of reporting. During the month of May, it is critical to recognize certain elements of maternal mental health that must be addressed:

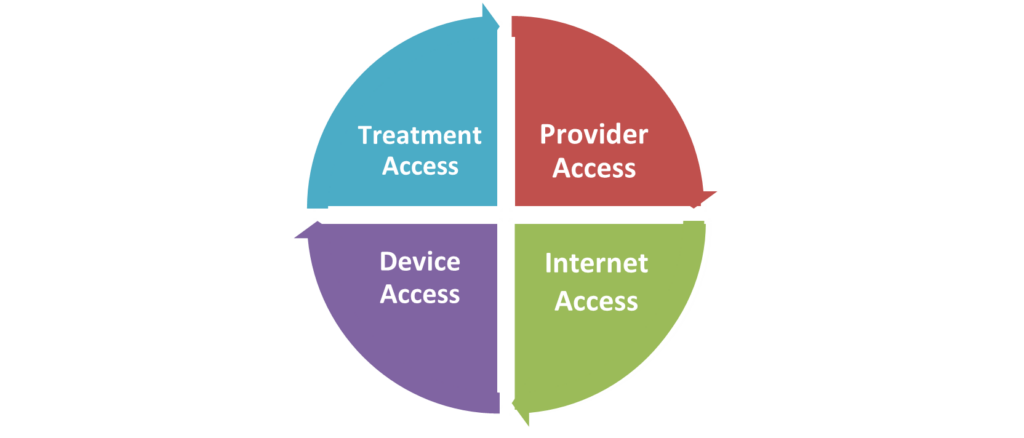

Telehealth Access Wheel: Foundational Needs for Telehealth (NPIC, 2023).

This month, it is essential that we create space to discuss maternal mental health, and to develop sustainable strategies for treatment and maternal well-being. Whether that be in a prenatal visit, admission to Labor and Delivery, during a NICU visit, or in the community, as a nation we must be prepared to destigmatize maternal mental health, assure equitable care and access, and create a compassionate course of treatment for women and birthing people who continue to suffer in silence.

References

Devakumar D, Selvarajah S, Shannon G, et al. Racism, the public health crisis we can no longer ignore. The Lancet. 2020;395(10242):e112-e113. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31371-4

Ouyang JX, Mayer JLW, Battle CL, Chambers JE, Salih ZNI. Historical Perspectives: Unsilencing Suffering: Promoting Maternal Mental Health in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. NeoReviews. 2020;21(11):e708-e715. doi:10.1542/neo.21-11-e708

Patrick SW, Schiff DM, Prevention C on SUA. A Public Health Response to Opioid Use in Pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-4070

Patrick SW, Barfield WD, Poindexter BB, Committee on Fetus and Newborn C on SU and P. Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5). doi:10.1542/peds.2020-029074

Kendig S, Keats JP, Hoffman MC, et al. Consensus Bundle on Maternal Mental Health. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):422-430. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001902

Pescosolido BA. The Public Stigma of Mental Illness: What Do We Think; What Do We Know; What Can We Prove? J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(1):1-21. doi:10.1177/0022146512471197

Mendelson T, Cluxton-Keller F, Vullo GC, Tandon SD, Noazin S. NICU-based Interventions to Reduce Maternal Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1870

Overview

May is Maternal Mental Health Month, which provides an opportunity for providers, patients, communities, and activists to engage in discussion and dialogue about the importance of recognizing maternal mental health as an unmet, urgent public health need. Compound this maternal mental health need with the public health crisis of racism and a stark picture emerges of women and birthing people in need of tremendous support. There are many facets that must be addressed within maternal mental health—access to care, transportation, stigma, insurance coverage, stable housing, to name a few. An area of concern that has been identified is that of opioid use disorder during pregnancy. A greater prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, physical and sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and chronic pain disorders likely contribute to disproportionate rates of opioid use and misuse in women and particularly women during pregnancy. Beyond opioid use are other substances that are used frequently to mask mental health symptoms that can be treated by other means. But that treatment costs money and access can be sparce depending on location and availability of providers.

The National Perinatal Information Center continues to track maternal mental health outcomes, including substance use disorder. In 2019, substance use disorder (ICD O99.3XX) was coded in 1.9% of patients (n = 334,402) and by September 2023, 2.3% were coded with substance use disorder (n = 325,195). While that number might not seem high, it continues to reinforce the need to remain vigilant in assessing patients in the prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum period.

In the time period October 1, 2021 through September 30, 2022, 30-40 patient records were coded with postpartum psychosis (ICD -10 F53.1). In seeing this information, I thought about the patient behind the data. I wondered what their support systems were like. I wondered if they had support, or if they were alone in their suffering. I hope these women had what they needed to not only bring life into this world, but also had those to support them while they nurtured that new life.

Maternal mental health directly impacts the outcomes of a newborn. Perinatal mood disorders are some of the most identified maternal mental health concerns and are associated with increased risks of maternal and infant mortality and morbidity and are recognized as a significant patient safety issue. In addition to perinatal mood disorders, there are other mental health diagnoses that must be appreciated, including pre-existing psychiatric illness (major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, etc.) that often is underreported and undertreated due to stigma and fear of reporting. During the month of May, it is critical to recognize certain elements of maternal mental health that must be addressed:

- Destigmatize mental illness: Stigma is a complex phenomenon, that has three different types: public, self and institutional. Self-stigma develops from shame, blame and internalization of mental illness, which is most often fueled by public and institutional stigma. Supporting women and birthing people experiencing maternal mental health illness, and reducing shame and self-blame, is critical in achievement of treatment regimens and continued engagement with healthcare providers.

- Screening women for mental health during the postpartum period: NICU’s across the United States have begun to engage in various forms of screening and intervention to assist in reducing stress and depressive symptoms in mothers during newborn admission. In many cases, maternal mental health concerns remain under identified and undertreated during a NICU stay, which can have deleterious effects on the offspring, both in short-term outcomes while in the NICU as well as long-term neurodevelopmental and behavioral outcomes. Mendelson et al performed a systematic review and metanalysis of NICU programs designed to evaluate for postpartum depression and anxiety and found it increasingly important to evaluate maternal mental health during NICU admissions to assure engagement and understanding of treatment and discharge plans.

- Disparities in maternal mental health treatment: Overall, Black women are 3-4 times more likely to die during childbirth or within the first year after delivery. Increasingly, studies describe inequity in mental health screening, identification, and treatment for women of color and other vulnerable populations. Sidebottom and colleagues described the findings of their study in which African American, Asian, and non-white women were less likely to be screened for postpartum depression than their white counterparts. In addition, this study also revealed that women insured by Medicaid and other state programs were less likely to be screened than those women with private insurance.

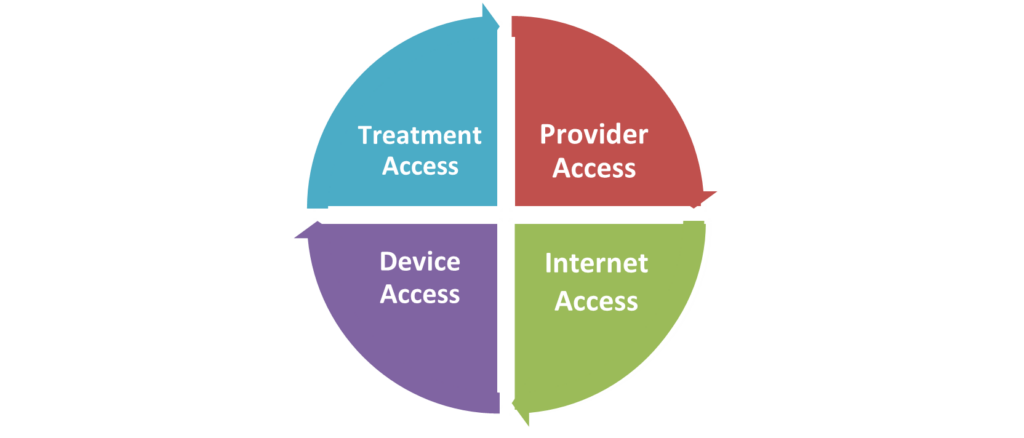

- Access to care: Psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and others can be difficult to access, particularly in rural environments. Paying for these services can be difficult, if not impossible, as many providers may not accept Medicaid or patients may not have the means to cover services not covered by insurance. Credentialed/certified community health workers (CHW) can be an invaluable resource for supporting patients in seeking resources for maternal mental health care. Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioners (PMH-NPs) can also be a vital community resource for patients. Supporting legislation to provide avenues for advanced practice is key in further developing this critical community resource. Advocating for coverage for postpartum maternal mental health is critical to supporting mothers in our communities. Finding new and innovative ways of using and supporting telehealth and digital access to maternal mental health access is imperative. But this access to mental health is dependent upon providers, access to broadband, technology, treatment (medication/therapy) and the cycle begins anew.

Telehealth Access Wheel: Foundational Needs for Telehealth (NPIC, 2023).

This month, it is essential that we create space to discuss maternal mental health, and to develop sustainable strategies for treatment and maternal well-being. Whether that be in a prenatal visit, admission to Labor and Delivery, during a NICU visit, or in the community, as a nation we must be prepared to destigmatize maternal mental health, assure equitable care and access, and create a compassionate course of treatment for women and birthing people who continue to suffer in silence.

References

Devakumar D, Selvarajah S, Shannon G, et al. Racism, the public health crisis we can no longer ignore. The Lancet. 2020;395(10242):e112-e113. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31371-4

Ouyang JX, Mayer JLW, Battle CL, Chambers JE, Salih ZNI. Historical Perspectives: Unsilencing Suffering: Promoting Maternal Mental Health in Neonatal Intensive Care Units. NeoReviews. 2020;21(11):e708-e715. doi:10.1542/neo.21-11-e708

Patrick SW, Schiff DM, Prevention C on SUA. A Public Health Response to Opioid Use in Pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-4070

Patrick SW, Barfield WD, Poindexter BB, Committee on Fetus and Newborn C on SU and P. Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5). doi:10.1542/peds.2020-029074

Kendig S, Keats JP, Hoffman MC, et al. Consensus Bundle on Maternal Mental Health. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):422-430. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001902

Pescosolido BA. The Public Stigma of Mental Illness: What Do We Think; What Do We Know; What Can We Prove? J Health Soc Behav. 2013;54(1):1-21. doi:10.1177/0022146512471197

Mendelson T, Cluxton-Keller F, Vullo GC, Tandon SD, Noazin S. NICU-based Interventions to Reduce Maternal Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1870