Respectful Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Respectful Care continues to be a priority for maternal and neonatal outcomes, particularly with the continued disparities described throughout the literature, including significant outcome disparities found within Black and Brown women and birthing persons, particularly maternal care and NICU care.

Posted under: Other, Quality of Care

It only makes sense to create newborn and NICU patient care bundles that are similar in nature to their maternal patient care bundle counterparts. After all, standardization and reducing variation are key to patient safety outcomes. The NICU is a natural next step in creating and cultivating patient safety bundles.

Patient safety bundles include the following domains:

- Readiness

- Recognition

- Response

- Reporting/Systems Learning

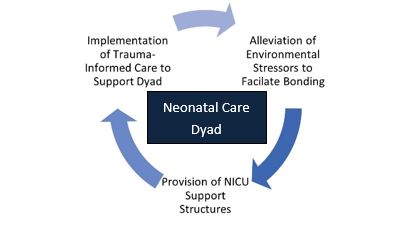

- Alleviation of Environmental Stressors: Providing support to the mother/birthing person to assure opportunities for bonding and care provision are essential. Transportation, food security, and the care of other dependent children as needed for frequent visitation to the NICU provides stability. Financial challenges compound these issues and further accelerate the disparities that are found within neonatal care. The promotion of dignity, autonomy and the ability to care for a sick newborn amid turmoil, such as an unexpected admission to the NICU, cannot be overstated.

- Provision of a NICU Family Navigator/Support Structures: The ability for a mother/birthing person to achieve the highest levels of autonomy during a NICU stay relies on the ability to fully comprehend and understand the course of care. A NICU Family Navigator or NICU Family Support Program can facilitate communication and ensure that every newborn and family are assured the same level of care and discharge planning. Lake and colleagues described disparities in NICU outcomes related to race, and failure to offer the same level of discharge care to all families is antithetical to the Respectful Care model. Any differences in care, specifically racial and/or ethnic outcomes discovered during inpatient care or during the discharge process should be immediately evaluated. The inclusion of postpartum doulas to offer support for the woman/birthing person during the NICU stay should be encouraged. (If you have not thought about using Postpartum doulas in your NICU as a support for your parents, now is the time).

- Trauma-Informed Care: Trauma-informed care is an essential principle of the Respectful Care model. Facets of trauma-informed care, such as previous experiences of trauma and subsequent response and reducing the impact of a current trauma (such as an unexpected admission to the NICU) provide a meaningful foundation to the care of mothers/birthing people during a stay in the NICU. Maternal/newborn separation can exacerbate trauma, and facilitation of visitation and information is key. Again, identification of environmental and social/structural determinants of health and their mitigation can ease the impact of further trauma to a family unit. These elements are cyclical, and all serve as conduits within a Respectful Care paradigm.

How much does it cost to park in your hospital parking garage? How much is a bottle of water or a small meal in your hospital cafeteria? And if a baby is in the NICU for weeks, what does that cost? Childcare for those children at home? Lost hours at work? The trauma of an unexpected NICU admission can be but the very start of a perpetual traumatic experience for a family.

The Black Mamas Matter Alliance describes best practices for holistic maternal and neonatal care:

- Addresses gaps in care and ensures continuity of care

- Affordable and accessible care

- Ensures informed consent

- Confidential, safe, and trauma-informed

- Provides wraparound services and connections to social services

So, let’s start a checklist for Respectful Care in the NICU:

Centering the baby and family for all care and decisions

Dignity and autonomy

Informed consent

Shared decision-making

Equitable access to pain management

Access to Postpartum doulas

Access to Community Health Workers

Postpartum depression assessment of mother and partner with appropriate referrals

24-hour access to baby

Parental presence during resuscitation

Assessment of childcare needs

Assessment of transportation availability

Assessment of nutrition

Equity in access to lactation support and donor milk

A home transition plan that respects and incorporates the culture, values, and lived experience of the family

Ability to measure Respectful Care and its impact on patient outcomes

Building respectful care into any NICU patient safety bundle should be a first step. I hope to hear from you and let’s continue to grow a new and emerging model of Respectful Care in the NICU.

References

1. Moridi M, Pazandeh F, Hajian S, Potrata B. Midwives’ perspectives of respectful maternity care during childbirth: A qualitative study. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0229941. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229941

2. Sacks E, Kinney MV. Respectful maternal and newborn care: building a common agenda. Reproductive Health. 2015;12(1):46. doi:10.1186/s12978-015-0042-7

3.Howell EA. Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(2):387-399. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000349

4.Harvey SA, Lim E, Gandhi KR, Miyamura J, Nakagawa K. Racial-ethnic Disparities in Postpartum Hemorrhage in Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and Asians. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(5):128-132.

5.Km M, A K-D, R K, et al. Racial Differences in the Cesarean Section Rates Among Women Veterans Using Department of Veterans Affairs Community Care. Med Care. 2021;59(2):131-138. doi:10.1097/mlr.0000000000001461

6.Sacks E, Kinney MV. Respectful maternal and newborn care: building a common agenda. Reproductive Health. 2015;12(1):46. doi:10.1186/s12978-015-0042-7

7.Glazer KB, Sofaer S, Balbierz A, Wang E, Howell EA. Perinatal care experiences among racially and ethnically diverse mothers whose infants required a NICU stay. Journal of Perinatology. Published online July 15, 2020:1-9. doi:10.1038/s41372-020-0721-2

8.Sigurdson K, Morton C, Mitchell B, Profit J. Disparities in NICU quality of care: a qualitative study of family and clinician accounts. Journal of Perinatology. 2018;38(5):600-607. doi:10.1038/s41372-018-0057-3

9.Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Lewis Johnson T, McLemore MR, Neilson E, Wallace M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. Journal of Women’s Health. 2020;30(2):230-235. doi:10.1089/jwh.2020.8882

10.Barfield WD, Cox S, Henderson ZT. Disparities in Neonatal Intensive Care: Context Matters. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2). doi:10.1542/peds.2019-1688

11.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, et al. Guidelines for Family-Centered Care in the Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adult ICU. Critical Care Medicine. 2017;45(1):103-128. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169

12.Sanders MR, Hall SL. Trauma-informed care in the newborn intensive care unit: promoting safety, security and connectedness. Journal of Perinatology. 2018;38(1):3-10. doi:10.1038/jp.2017.124

13. Black Mamas Matter Alliance. Setting the standard for holistic care of and for Black women. http://blackmamasmatter.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/BMMA_BlackPaper_April-2018.pdf