Quality Improvement in Maternal and Newborn Care: No, You Don’t Have to Run for the Hills

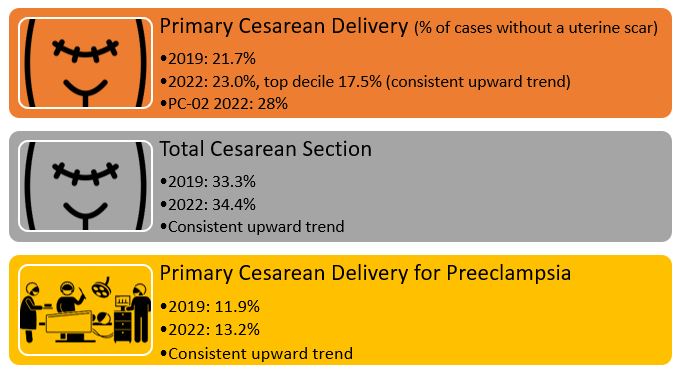

Most states have developed perinatal quality collaboratives to enhance hospital care quality for maternal and newborn care. While some states are further along in their journey, others continue to develop their programs. Where are you in your own QI journey?

Posted under: Maternal Health, Quality of Care

If you are still here reading this, and haven’t run for the hills, that’s a good sign.

If you are seeking refuge far, far away from this conversation, you are not alone. But maybe we can get you to take a peek every once in a while.

Many QI definitions, with nuances and variations, perhaps create more confusion than most would like when exploring quality improvement.

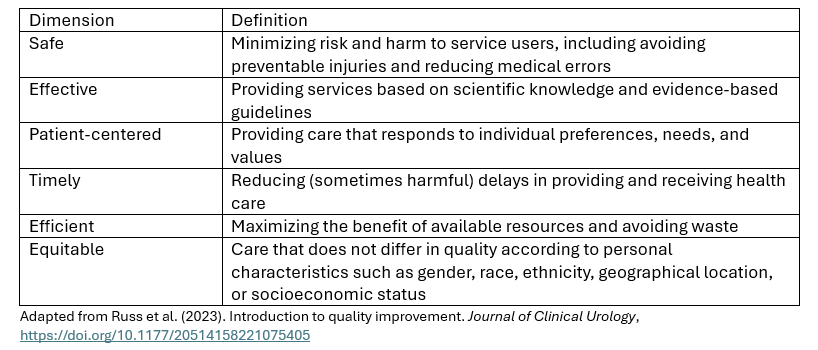

But let’s start with this definition from the World Health Organization (2024): “The degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge”.

Within this definition, there are six (6) dimensions of quality:

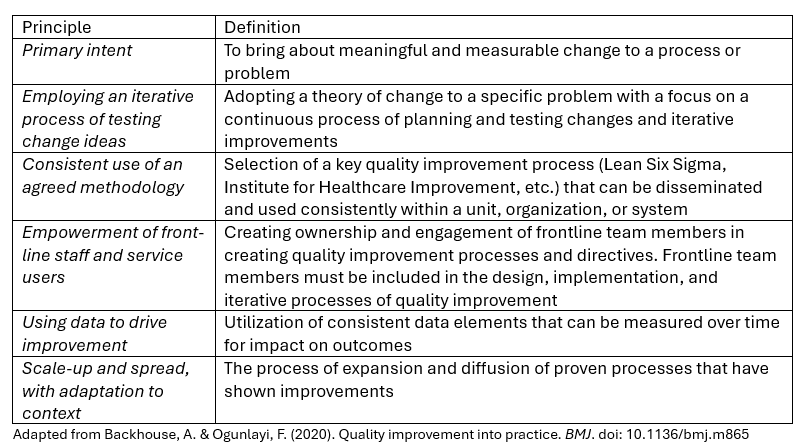

However, perhaps even more critical is the QI process. And I would wager this is where most go running for the hills. But before you begin your sprint, perhaps there is another way to think about this…to think about QI through the lens of the principles, as opposed to considering the myriad of definitions.

Most hospitals and systems adopt a quality improvement process to support the foundations of their improvement programs. What QI process does your hospital use? Is it user-friendly? Can your teams describe the process readily when asked? How are results shared among teams and the organization? The more complicated the process, the less likely the program will have long-term sustainability.

Interestingly, most quality improvement programmatic definitions do not include involving patients or communities as part of the QI journey. While we are becoming more comfortable with the direct involvement of those most impacted by our work, don’t forget that any quality improvement initiative that directly impacts patients should include patients in the design.

This past week, I spoke with Dr. Pattie Bondurant, DNP, RN, ANLC, FAAN, CEO of TransForm Healthcare Consulting, LLC, for the NPIC Safe and Sound© Podcast. Dr, Bondurant is a neonatal quality improvement expert who has spent years creating pathways to elevating care for babies nationwide. During our conversation, I asked about the future state of quality improvement: “We as a system must understand how important [quality improvement] is and where our professional accountability lies, not just to our patients and our family, but to one another, to our physician colleagues, to our nursing colleagues, to the staff who empowers us to make sure that they can practice as safely as possible.”

When you think about it, maybe it is genuinely that simple. Quality improvement involves empowering one another to practice as safely as possible in creating the highest quality of care using evidence-based tools, resources, and data.

Even if you still might be more comfortable “in those hills,” I hope you will join us in creating environments supporting care teams, patient outcomes, and maternal and neonatal quality improvement essentials.

Want to learn more about elevating your maternal and neonatal quality improvement program? Connect with the National Perinatal Information Center at inquiry@npic.org.